When looking back on early rock and roll, the alternating lenses of late-century nostalgia and recent historical revisionism tend to obscure the fact that a lot of the actual music made in the genre’s formative years was completely demented.

The 1980s’ massive market for 50’s nostalgia - which was driven by generational trends as much as it was by the death of Elvis in 1977 - provided a squeaky-clean origin story for the baby boomers and a massively profitable distraction for Americans exhausted by the cultural upheavals of the 60’s and 70’s. The popular conception of the 1950s as an essentially peaceful and prosperous American Golden Age begins here, with the cultural exploration of movies like “Back to the Future,” “The Buddy Holly Story,” and “Grease” providing a sort of organizing principle for boomers aging into a brutally cynical post-Vietnam world. Nostalgia is propaganda; in this case, it encourages the idea that the mid-century - because it was a time when such a culturally influential generation was young - was an innocent time, a purer time when American lives more closely adhered to American values.

The last decade or so has seen a massive reevaluation of that myth, and of all national myths. A more historically-conscious generation of Americans has begun to find it impossible to reconcile the old party lines about democracy and equality with the obvious evidence of institutional racism, class disorder and political dysfunction that bombards every second of our public consciousness. This isn’t new stuff, by any means - but as media control becomes more and more fragmented, the public narrative becomes less cohesive and the handlers begin to lose control of the monster they’ve created.

This has resulted in the not-so-shocking realization that the cultural vanguards of the ruling class have not always been the best representatives of our better angels. The old heroes are the new villains, which, in a country whose entertainment industry is the substitute for a national identity, has ended up as a colossal crisis. The Elvises and the John Waynes and the Marilyn Monroes that have been defied in the national consciousness have turned out to be neither hero nor villain but messy contradictions like the rest of us and it’s resulted in something like a manic-depressive episode resonating simultaneously in three hundred million souls - especially given the fact that a world governed by social media has failed to provide us with any better role models.

This is the central anxiety of the history of early rock and roll music, which has been variously portrayed as cultural theft from the blues and R&B, the ultimate artistic expression of racist white perverts, an explosively dangerous tool for youth liberation, a capitalist merchandising hustle, and a bizarre aberration in the history of popular art. Is is, of course, all these things and none of them. In times of crisis we grasp at history in order to steady our perspective; but history and culture itself is not objective and idol worship will buck you like a horse. The essential agony of our national identity is that two things can be true at the same time - that the lofty virtues that define our national purpose are still virtuous, regardless of the fact that the dudes who conceived of them were extremely shitty. The whole point is that we have the responsibility to guide ourselves towards greater things.

Which is why rock and roll is the perfect topic for an exploration of American culture. At its most basic, early rock was a mongrel art form that blended gospel, blues and country music without fully assimilating any of them. By the time rock and roll materialized in the mid-1950s, both blues and country had themselves been organized into segregated industries, which synthesized various forms of ethnic music into sales categories that were in line with the racist principles of American society at large. I’ll get more into this stuff when we start to talk about Elvis Presley; for now, it’s important to note that while racism was very much at work throughout the whole history of rock, its first idea was that these two dominant root forms of country and blues didn’t need to be segregated. These were traditions that were both rooted in folk, shared a Southern identity, and were easily performed by amateurs - it made sense that artists from each tradition should be able to develop one another’s ideas.

This was an extremely powerful idea that arguably fully loosed the energies of the Civil Rights movement, the Sexual Revolution, and certainly the drug culture and anti-war movements a decade down the line. And it provided a new template for national expression; the resulting decades of debate over who owns the origins of rock and roll are really just a demonstration of its domination over the American psyche. Glancing at my record shelf, I am reminded that this kind of music’s “Big Bang” can arguably be traced back to Little Richard, Elvis, Ray Charles, various Delta blues singers, Savoy Records, Big Maybelle, the Apollo Theater, and Hank Williams - and that’s just the folks whose albums we still have to talk about.

Once again, more than one thing can be true at the same time. Our fixation on these origins ignores the fact that the cultural behemoth that was “rock and roll” wasn’t drawn up and executed by a single person, overnight.* It also ignores the fact that the cross-pollination that occurred during the early rock years was often radical, inventive, and liberating.

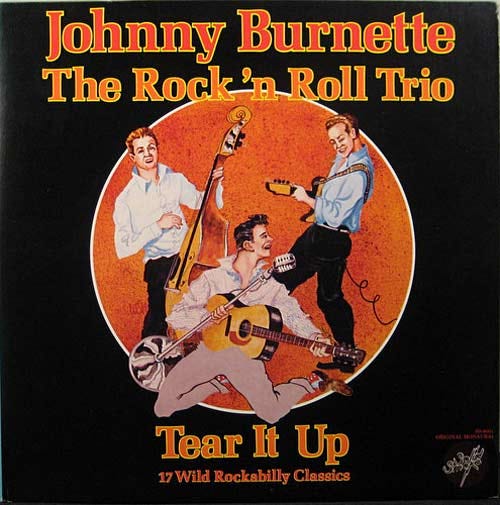

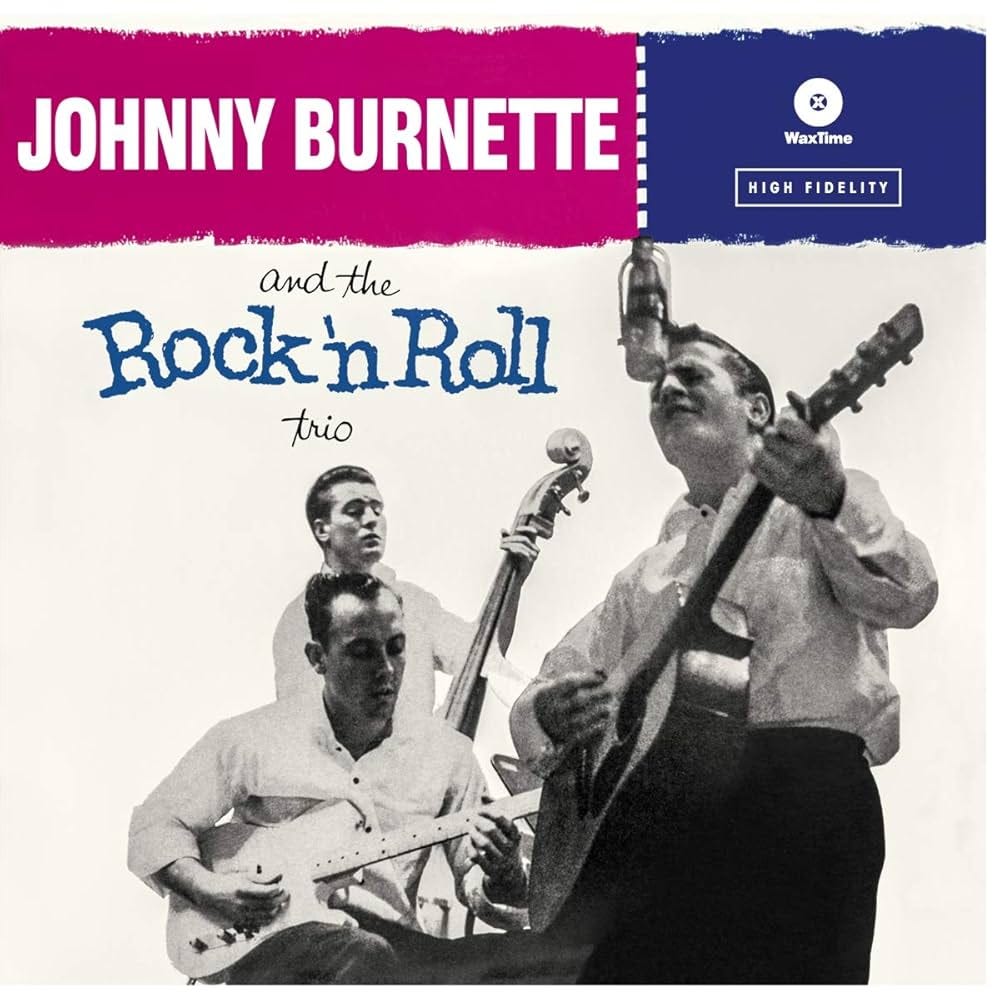

Which gets us to this week’s record. This Johnny Burnette/Rock and Roll Trio LP is a budget compilation from the late 70’s that gathers material a handful of recording sessions done by this Memphis group from 1955-57. I picked this up somewhere because of my familiarity with the Rock and Roll Trio’s absolutely insane self-titled rockabilly disc from Coral Records, much of which is repackaged here.

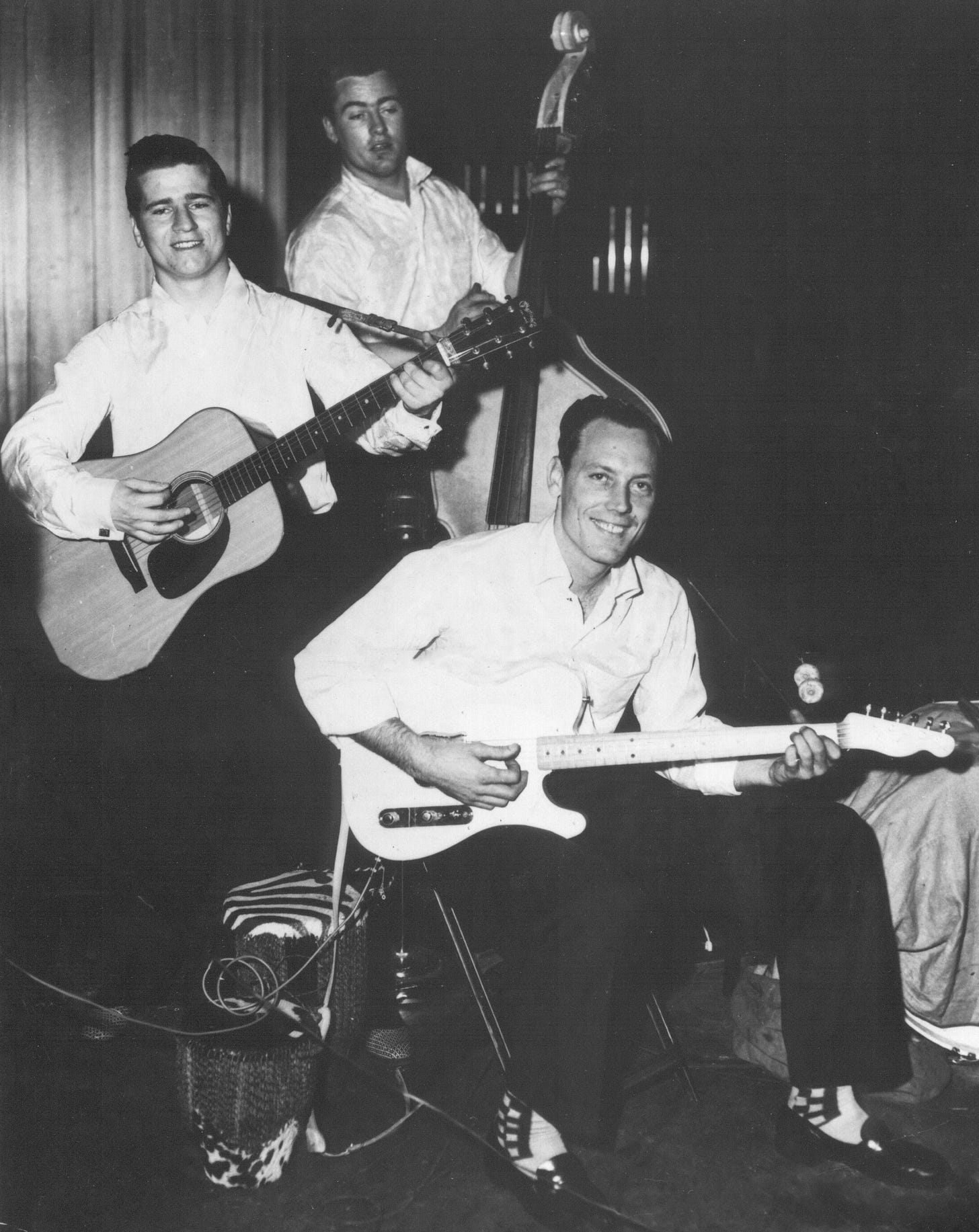

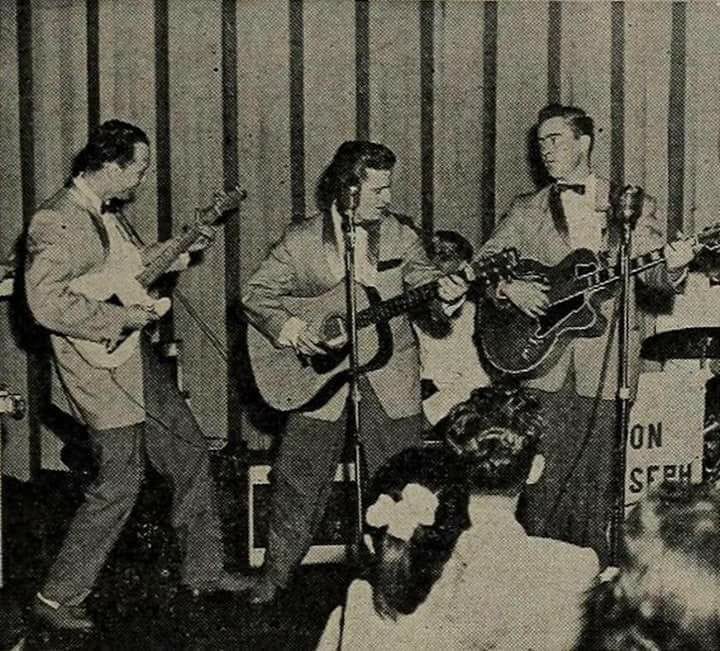

The RnR Trio is one of the great Memphis bands. They had a bit of a Forrest Gump thing going in the way they brushed up against history; guitarist Paul Burlison cut his teeth as a live session guy for Howlin’ Wolf, and the Trio was passed up by Sun Records in the wake of Elvis’ success. They were broadcast on national television on September 9th, 1956 - which was the same day that Elvis appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show and ushered the nation into a recognizably modern world. Their impatience to promote their material led to their signing with the tiny Coral label, instead of the giant Columbia, who had been courting them. Friction between Burnette and his brother (and bandmate) Dorsey resulted in a fistfight that broke them up exactly one week before they were supposed to film a movie with the legendary DJ Alan Freed. And just when British groups like the Beatles and Yardbirds began to popularize these guys’ songs, Johnny Burnette himself died in a boat crash.

Having dissolved before any member could fall victim to their own success or spiral into paranoid acts of violence or leave a legacy in Christmas music or go country or marry their teenage cousin, the Trio’s catalog is pretty self-contained. There’s not a lot of material for the mid-century reissue vultures to have picked over, and the result is that these guys aren’t exactly a household name. And it doesn’t help that their best material edges up against the psychotic - the stuff from the Coral LP is startlingly modern in its vocal delivery and guitar texture. Having accidentally discovered fuzz guitar after knocking a tube loose from his amp, Paul Burlison’s guitar tone on tracks like and “Lonesome Train (On A Lonesome Track)” is absolutely menacing and far more hard-edged than any of his rockabilly contemporaries. His sound is more in line with blues artists like Pat Hare and Otis Rush than the country-influenced players of his day, and Burnette’s deranged, agonized yelp is a reminder of why this kind of music was considered controversial back in the fifties. The wimpy teenage overtures of that era’s pop music are no match for the brazenly lustful and lascivious snarls of a track like “Train Kept A-Rollin’.” It anticipates punk and new wave and has held up a lot better than, say, Brenda Lee; when the Trio showed up in the studio and was confronted with a 32-piece orchestra, they fired everyone but the drummer and got to work.

I couldn’t find many biographical details about Burnette, so I couldn’t tell you whether or not he, like so many of his contemporaries, was a very problematic person. One listen to his vocal performance on “Train Kept A-Rollin’” seems to indicate that he was at least Satanic; there’s something about this recording that still has the power to shock nearly seventy years down the line. So why doesn’t this entire record hit as hard as the Coral LP?

Since most of the material on this reissue is drawn from multiple sources, the sequencing is weird and the overall effect is kind of hit or miss. I tend to recommend this group to people who are ambivalent about rockabilly - so it’s a shame that about half of the tracks on this disc are fuckin’ nuts, while the non-album ones pale in comparison. The back cover lists all the recording information for each song, including the recording dates, which tells us that something happened to these guys between May and July of 1956 that imbued their sound with some kind of voodoo. The tracks from May of that year (except the banger “You’re Undecided,” which clearly inspired one of my favorite garage rock classics “Take A Heart”) are undistinguished rockabilly workouts, while the tracks from July are completely gothic and evil. On “Please Don’t Leave Me,” Burnette transforms a pretty banal lost-love lyric into a menacing two-note tribal chant, while on “Rock Billy Boogie,” the fuzzed-out minor key guitar makes the titular “boogie” sound like something going wrong in a remote swamp. On “Drinkin’ Wine, Spo-Dee-O-Dee,” the band appears to have already drank plenty before getting in front of the microphone.

Whatever black magic these dudes conjured up was gone by the next spring. The few cuts from March 22, 1957 on side two of this album are so disappointing and totally boring that my copy of it is pretty much pristine. Pristine - as in, never been played. Limp and uninspired, the three songs from 1957 that are included here find the band creatively bankrupt and obviously exhausted. I do not like this music - I actually turned my stereo down at this point so my neighbors couldn’t hear it and wonder to themselves if I’m some kind of an idiot.

After the band broke up, its members pursued solo careers. Dorsey Burnette toiled in the shadow of his brother for a few years, putting out a few tortured pop and country-oriented LPs and singles for small labels before unexpectedly cutting some weird sides for Motown. Johnny Burnette only lived a handful more years and also pursued pop; he released a few bad records and a couple singles of very questionable taste, like “You’re Sixteen,” which carry no trace of the primal howl of the Trio and are more in line with the kind of shit that makes you cringe when it’s played on the radio at your favorite diner. Do yourself a favor - get the Coral Records LP, crank up “Honey Hush,” and forget the rest.

*If I were being forced, at gunpoint, to name a single source track, I’d probably pick “The Fat Man” by Fats Domino; the ways in which it diverges from blues and gospel are easy to hear, but hard to explain. Some people will tell you it’s Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s “Strange Things Happening Every Day,” but I think the lyrical content puts it firmly in the gospel category. Another contender is Arthur Crudup’s “It’s All Right,” famously covered by Elvis - but it too deals in the blues “floating verse” lyric tradition. Most folks agree that it’s “Rocket 88,” featuring a young Ike Turner.

As always, those of you who use Spotify can follow along by saving our ever-growing Dollar Bin Blues playlist, which can be found here.