“We got two honkies out here lookin’ like Hasidic diamond merchants… they look like they’re from the CIA or something. The tall one wants white bread. Toasted. Dry. Nothin’ on it. And the other one wants four whole fried chickens and a Coke.”

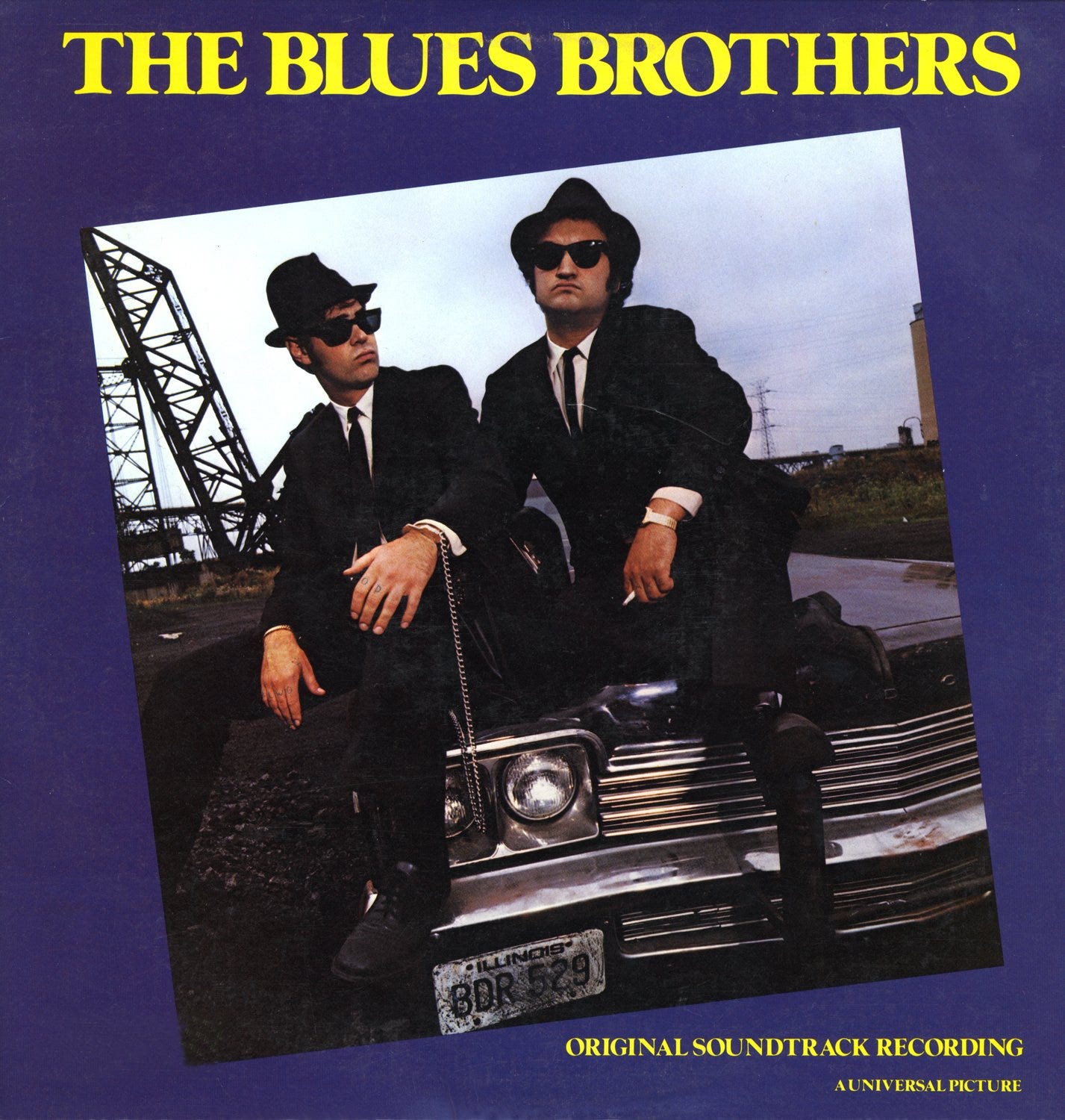

It’s the Blues Brothers!

If you were looking to study the ways in which we ritualize art in our daily lives, look no further than “The Blues Brothers,” a 1980 film that I have seen about seven hundred times and can quote more extensively than Shakespeare. I love this movie; despite its flimsy plot and its total reliance on extravagant musical numbers and ridiculous car chases, it’s one of those artifacts that is as fresh now as it was when I was twelve years old.

As a kid I was totally galvanized by this film - it was one of my first exposures to blues of any kind, a foundational form of American music that is incalculably important to any understanding of our national culture but nevertheless was not extremely visible in suburban New Hampshire in the early 2000s. I grew up in a part of the world that was founded by the Puritans, who had no major art or music culture to pass down to us in the present. Unlike many other parts of the United States (like, say, Chicago), northern New England doesn’t really have a surviving musical heritage - unless you count the extremely popular and progressive genre of sea shanties. So pretty much everything I could get my hands on as a kid felt new and exciting, so long as you couldn’t already hear it on the radio. Given the kind of programming available to me back then, that meant that everything besides classic rock was, essentially, alien. So in a place as completely and homogeneously white, middle class, and middle aged as New Hampshire, even a track as evergreen as “Boom Boom” can seem revolutionary. No matter that it’s included in the middle of a Saturday Night Live comedy; teenage rebellion has never been so easy.

So it’s funny, but also somewhat appropriate for this blog, that our first discussion about blues music is going to happen in conjunction with the soundtrack from The Blues Brothers. The blues, like the country music we started to talk about last week, evolved from ancient sources and ethnic styles and is subject to a lot of hand-wringing about authenticity. In the age of Spotify and YouTube, we have access to the entire canon of recorded sound and anybody with an internet connection can educate themselves on the ways in which music has evolved over time. All music history is, on Wikipedia, laid out before us, and we have access to a universe of critical perspectives that tell us who innovated and who exploited and who had artistic integrity and so on.

It’s a privilege to be able to engage with the both the purest and most far-out possibilities of every kind of music for essentially free and have generations of writers and thinkers on hand to help us interpret what we’re listening to. But it wasn’t always that way - for most of the last century, a lot of what we consider art came to us passively, on the radio and in advertising media and on television. When this sort of media dictates what the general public does and does not see, a lot of of stuff comes to you out of context or is subject to the censorship of a small group of curators - or else is extremely watered down in order to appeal to the broadest viewership base possible.

Given that the Blues Brothers (John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd) were a pair of famous white comedians, whose work was primarily in television, and that their project started as a Saturday Night Live bit titled “Howard Shore and His All-Bee Band,” it was natural to wonder about their artistic intent. Musicians who worked with the Brothers’ band were accused of being sell-outs, and critics dismissed the music itself as exploitative and crass. Their popularity as a music act would have been impossible without their SNL cred, and the suit/hat/sunglasses shtick would have been a bad joke if it weren’t for the fact that, well - it was a bad joke. And many reputable sources still list them as a fictional band, in spite of the fact they performed regularly, had one of the all-time great backing groups, and even opened for the Grateful Dead at the closing of the Winterland Ballroom.

But ultimately these dudes operated as a sort of Trojan horse. Using their influence on the relatively “safe” medium of television, they introduced a huge swath of people to blues, soul, and R&B and - with their film - gave some of the titans of these genres a late-career boost. These dudes were blues obsessives, with a deep understanding of the form and its history, and understood the ways in which its basic elements had evolved into soul and R&B over the course of the 20th century.

This soundtrack operates like something of an R&B music revue, in which Belushi and Aykroyd use the Blues Brothers bit to bookend an introductory journey through that history. Obviously this disc is not comprehensive; it is a movie soundtrack, after all, and the material here ignores all the music in the movie that isn’t performed by the Blues Brothers band. Folks interested in the “real” groups - the Stax-era Sam & Dave and Otis Redding material, as well as definitive cuts of “Let The Good Times Roll” and “Boogie Chillun” (not to mention that “Boom Boom” cut) - will have to head back to the record store. Those interested in the straight natural blues will have to go, too, as The Blues Brothers stuff that is included - save for the western shlock “Theme From Rawhide” - skews more towards the soul end of the R&B spectrum. Besides that, the mixes on the LP are totally different from the ones in the movie, and some of the tracks are freighted with extra overdubs. But the music is fun, the session players (including half of the M.G.s!) are some of the best of the day, the guest artists are clearly having a good time, and the soundtrack and the film itself are enjoyable links between this most important roots music and the popular culture from which its faded.

Opener “She Caught The Katy” is a great example of the ways in which this band owns and overcomes its contradictions; this uptown blues has the kind of tight arrangements and horn interplay wouldn’t be out of place on The Band’s Northern Lights, Southern Cross record, but miraculously doesn’t feel like a rip-off or an artifact. The band is totally committed, and why wouldn’t they be? The players this disc have credits on records by Memphis Slim, Howlin’ Wolf, Yoko Ono, Dr. John and countless others; Steve Cropper and Duck Dunn alone played on hundreds of classic Stax records. The fact that they backed Otis Redding should, in itself, tell you what serious operators these dudes were. And while the vocals on this cut are credited to the “Jake” character, that doesn’t disguise John Belushi’s actual vocal chops, which are faithful enough to make you forget that the dude singing is the same one who played Bluto in “Animal House.”

Belushi keeps step and holds his own alongside Ray Charles and James Brown who, on side A, lead a tongue-in-cheek exploration of the way that gospel sounds gradually evolved into early rock and roll (“The Old Landmark” and “Shake Your Tailfeather”). The sequencing is admittedly unfair to Aretha Franklin, who kicks off side B with a fair take on her classic “Think” only to be followed up by the cornball, Dan Aykroyd-led “Rawhide” - but Cab Calloway saves the program (as he does in the film) with the classic Cotton Club jam “Minnie the Moocher.”

It is silly stuff, and the production has that bouncy 80’s sheen. But if you make it all the way through this record, and ask yourself “who are these people?” or maybe “what the hell is this?” don’t abandon your curiosity. You’ve been given a fledgling’s first taste of the blues. Each of the guest artists here is like a carnival barker tempting you to explore their world a little further. Not to mention there’s a real undercurrent of passion that makes this music work even when it probably shouldn’t. I’m reminded of the Brothers’ first album Briefcase Full Of Blues in which the actual music is occasionally derailed by John Belushi’s commitment to crediting every performer in the band and every writer of every song. He does it in the movie, too - before performing “Sweet Home Chicago,” he gives a shout out to Magic Sam. Doesn’t it make you want to go out and listen to a Magic Sam record?

These dudes could be accused of a lot of things, but insincerity was not one of them. And while they were never in danger of outdoing the work of the artists they admired, the Blues Brothers did their part to keep the spirit of the music alive during an era of mass commodification. Working through SNL and Hollywood at the dawn of the 1980s, Aykroyd and Belushi would have been acutely aware of the ways in which talent was shaped and exploited by the media, and their work with this band may have began as some kind of a safety valve for them. Belushi himself seems especially liberated on these tunes - I like to imagine that maybe, in another life, he could have pursued his music and further developed the kind of performance career that gave him relief from the destructive pressure of celebrity.

Or maybe I just really love this movie. I re-watched it in preparation for this post, and I was reminded how much of the humor in it is relevant if you are, or have ever been, in a shitty band. The constant, buzzing anxiety of being a struggling musician is a wellspring for some of the funniest bits; obviously, the whole Bob’s Country Bunker sequence, in which the Blues Brothers desperately try to justify their mission by making some money at a beat-up roadhouse, should be familiar to anyone who’s ever organized their own tour (“This ain’t no Hank Williams song!”). And when the Brothers are “getting the band back together,” they naturally discover every single one of their old players performing or working in the service industry - still the last holdout of the desperate artist. But even small moments, like when the band arrives at the Palace Hotel Ballroom and express doubt it could ever be filled, come from a place of bitter humor. Dan Aykroyd’s love for this music drove this project more than anything, and knowing he was primarily responsible for the film’s script tells you everything you need to know: these guys were musicians.